“Mabon… is the immemorial prisoner whom the world has forgotten…,”

⁃ W. J. Gruffyth, Rhiannon, (1)

In his immense work Rhiannon, W.J. Gruffyth labored to piece out the ancient myth of the Brythonic Mother goddess and her son. He believed that the nucleus of the myth concerned the birth and abduction of the divine child from his mother and their eventual reunion, echoed in the indigenous tales of Pryderi, Gweir and Mabon. Mabon’s story as told in the Welsh Arthurian epic Culhwch ac Olwen can be summarized:

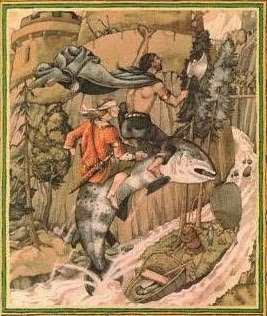

Mabon is required to hunt the fearsome boar Twrch Trwyth, but no one knows where he is to be found or even if he is living or dead. King Arthur’s knights consult successively older wild animals to ascertain his whereabouts. They are eventually led to the salmon of Llyn Llyw, who takes them on his enormous back through the River Severn to the fortress of Caer Lloyw (Gloucester) where Mabon is imprisoned. At this point it becomes clear that Mabon, still very much alive, has survived for epochs in captivity. The knights retreat to gather their forces, return to the secret prison and break through the wall, vanquishing the captors and freeing Mabon.

Gruffyth believed that this was one of several versions of the ‘Goddess and her Son’ myths. Bromwich and Evans, in their edition of Culhwch ac Olwen, strike a more skeptical pose regarding Mabon and his story told in the Arthurian text. (2) As they point out, Mabon is presumably the Middle Welsh derivation of the ancient deity Maponos. The deity had a cult center in the south of Scotland according to archeological evidence, and cannot be connected to Gloucester, in counterdistinction to Mabon in the text. They also point out that the triadic mention of Mabon and the triad ‘The Three Exalted Prisoners’ only occurs in later material that appear to be influenced by the Culhwch and Mabinogi traditions. They therefore remain unimpressed as to the antiquity of the Mabon episode. They contend furthermore that the immediately preceding quest for Eiddoel, who is likewise held hostage in Gloucester, is not only a double of Mabon but a more likely candidate for an original “Gloucester prisoner”:

“Variants of a name which is not dissimilar to Eiddoel are attested… where they are used to denote a duke and a bishop of Gloucester. Perhaps all the variants of this name which have been cited derive from an original famous prisoner who was incarcerated in Roman or sub-Roman times…” (3)

Owing to the shaky evidence for Mabon’s connection to Gloucester, and the traditions about his imprisonment, they propose that the Mabon incident is a secondary development to Eiddoel. While the suggestion of an ancient historical hero named Eiddoel is an interesting one, and with all respect due Bromwich and Evans, a thorough dismissal of Mabon and the incident found in Culhwch is not warranted. There remains a possibility that the story of ‘Mabon’s Rescue’ is an old and widespread narrative; one perhaps that even harkens to pre-Christian Celtic myths regarding Maponos.

‘…never has anyone been as imprisoned in an imprisonment as mournful as mine…’

⁃ Parker, Culhwch ac Olwen (4)

Bromwich and Evans point out that Mabon’s legend is linked to the international folktale of the Oldest Animal:

The episode of Mabon’s delivery is focused into high relief by prefixing to it the folk-tale of the ‘Oldest Animals’… Various scholars have indicated the antiquity and widespread distribution of the international tale of the ‘Oldest Animals’ (5)

The ‘Oldest Animals’ tale and its appearance in Wales, Ireland and elsewhere has been expounded at length already and there is little need to go at length about it right now. For further reading I would refer to the tremendous work of Elenor Hull. (6)

What has not received attention as far as I’m aware is that the “second half” of the Mabon tale also has an Irish equivalent, the actual rescue of Mabon from his prison in Caer Lloyw.

The Magical Prison of Oisín

Dated 12th c, the entry for Tipra Sen-Garmna in the Book of Leinster Dindsenchas, which Gerard Murphy attributes to older material, contains the tale of the kidnapped Oisín and his rescue by Finn. It can be summarized as follows:

The hag Sengarman and her monstrous son, as well as another hag and her son, go on a rampage throughout Ireland. Finn hunts for them, but they escape his detection by concealing themselves in an underground stronghold beneath a flowing spring. Later they find the young Oisín by the roadside and take him captive. One day as he is performing menial chores he manages to slip a handful of wood chips onto the water. The chips are carried down the river Feale (Co. Kerry) where they are spied by Finn, who knows they came from his son. Following the river he eventually discovers the submerged fortress. He gathers his forces for the attack, breaks in by digging through the wall and lays waste to the monsters. (7)

This tale certainly contains characteristics that echo the Mabon incident. Further, the ‘floating wood chips” motif occurs elsewhere in regards Finn seeking revenge for characters called MacNia and Mac Con, both of which share linguistic elements to the Welsh Mabon. (7) This recurring wood chips motif also prefigures the continental ‘Courtly Tristan’, wherein the hero summons his illicit lover by casting wood chips down a stream. Though before we discuss the Irish and Welsh material more fully, the obvious resemblance to another narrative poem concerning a monster and his mother should be evaluated: the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf.

Both the Irish and Anglo-Saxon depict conflicts revolving around a monster and his trollish mother making numerous destructive raids on human civilization, and the apparent imperviousness of the mother to non-magical weaponry; Criblach is able to defeat a hundred warriors until caught and slain by Finn, while the other mother Sengarman, though also possessing inhuman strength, is finally overpowered by him and garroted in the underground fight, paralleling Beowulf’s inability to cut the trolldame until he discovers the giant sword in the subterranean treasure horde, which only he is strong enough to wield. Gerard Murphy notes the similarities between the Finn Cycle tale and the English language Beowulf in his great treatise Duanaire Finn vol. III. first published in 1950. Upon his survey of comparanda, he felt that parallels stem from Celtic influence. (9) More recently, researcher Martin Puhvel (Beowulf and the Celtic Tradition, 2006) ultimately draws the same conclusions in his comparison of the Irish material, stating that the Anglo-Saxon poem is “fundamentally indebted to Celtic folktale elements”. (10) I hesitate to comment on how much of the Beowulf narrative springs directly from Celtic sources; but with the Welsh material to accentuate the argument, I feel safe in saying that the Celtic legends are indeed inviolate unto themselves; there is no reason to suspect that the Oisín and Mabon accounts have been influenced by Germanic language tales, including Beowulf. So now let’s explore the finer details present in the traditions surrounding the Gaelic and Brythonic heroes.

Mar Oisian an deigh nam Fiann

Like Oisian after the Fiann

⁃ Am Piobaire Dall (The Blind Piper of Gairloch, Scotland, fl. 1666-1754) (11)

As Gruffyth writes, Mabon is the ‘immemorial prisoner’, kidnapped in his infancy and surviving for untold centuries before his eventual rescue. This approximates traditions about Oisín. From the early extant sources Oisín is given the epithet of ‘dall’, meaning ‘blind’, and ‘goll’ meaning ‘one-eyed’. The usual implication in Irish (and Welsh?) is that the warrior is blind due to deterioration with age. (12) The blind hero Mogh Ruith is another example. By c 1200 the tradition of Oisín as possessed of surpassing longevity is brought into sharp focus in the text Acallam na Senórach, where he has lived for centuries and into the Christian period. (12) In the text, Oisín and his comrade Caílte wander Ireland recounting its mythical history to enrapt listeners. Another, unpublished recension makes Oisín the sole narrator. (14) A passage in the published Acallam depicts Caílte’s anxiety over retelling the details of the warrior band’s diverse exploits, bemoaning that he could not fully relate the vastness of their deeds even if:

‘…were there seven tongues in my head, and seven eloquences of the sages in each tongue…’ (15)

Bondarenko connects this quote with other Irish textual traditions, including the ‘secht solabra’ or “seven [poetic] eloquences” of Irish filed, and the passage found in the 9th or 10th c tract Airne Fíngein describing the ‘búada’, “wonder” of Fintan:

‘Tonight a beautiful spirit of prophecy in the shape of a gentle youth has been sent from the Lord, and a ray of the sun hits Fintan in his lips and it has extended through the trench of the back of his neck so that there are seven chains or seven good speeches of filid on his tongue since that time. And tonight the tradition and inherited knowledge was revealed.’ (16)

Fintan, several thousand years old, then emerges from his hiding place to recount the past wonders of Ireland, paralleling Oisín and Caílte in the Acallam. Fintan also bears the epithet ‘Goll’, and is connected with the Irish iteration of the ‘Oldest Animal’ tale. (17)

The belief in Oisín’s miraculous longevity was so popular that it survived into modern times in both Ireland and Scotland. Both Mabon and Oisín, then, are subject to near immortal lifespans.

There is no hunter in the world who can handle [Drudwyn the hound] except Mabon son of Modron, [and] Gwyn Myngddwn, horse of Gweddw – he is swift as a wave is he… Mabon [must] ride [that horse] to the hunting of Twrch Trwyth…

⁃ Parker, Culhwch ac Olwen, (18)

Mabon is shown in the Welsh text to be a mighty huntsman, an integral trait of Oisín as well. As early as the 8th c Oisín is depicted as a warrior-hunter, specifically in connection to boar hunting:

Then Finn found [Oisín] in a great wilderness. He was cooking a pig.

⁃ Meyer, The Quarrel between Finn and Oisín, (19)

We find that both heroes share one common story and two character traits. An interesting hypothesis arises from this, yet I admit hesitation to speculate much further on the matter, as we know little else about Mabon and less still concerning the mythology of Maponos. But I think we have amassed a body of evidence that points to an integrity in the Welsh legend as it has come down to us. I hope I have argued the case well, and shown that Bromwich and Evans’ skepticism, while still justified, is not conclusive.

(1) W.J. Gruffyth, Rhiannon, pg. 97

https://archive.org/details/w.j.gruffyddrhiannon/page/n105/mode/2up

(2) Bromwich et. al., Culhwch ac Olwen, pg. lxi

https://archive.org/details/culhwcholwenedit00brom/page/n63/mode/2up

(3) ibid, pp. lxi-lxii

(4) Parker, Culhwch ac Olwen

(5) Bromwich & Evans, pp. lxi-lxii

(6) Hull, The Hawk of Achill or the Legend of the Oldest Animals

(7) Gwynn, Metrical Dindsenchas, pp. 243-253

https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T106500C.html

(8) Murphy, pg. lviii

https://archive.org/details/duanairefinnbook03murpuoft/page/n63/mode/2up?q=Mac+Con

(9) Murphy, pg. xv

https://archive.org/details/duanairefinnbook03murpuoft/page/n19/mode/2up?q=Oisin

(10) Puhvel, Beowulf and the Celtic Tradition

https://muse.jhu.edu/book/40324

(11) Campbell, Popular Tales of the West Highlands, pg. 184

https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/pt4/pt410.htm

(12) As Murphy notes, “Guaire Dall, apparently a name given to Oisín in his old age.” Duanaire Finn vol. III, pg. 27

https://archive.org/details/duanairefinnbook03murpuoft/page/26/mode/2up?q=Dall

(13) Stokes, Acallamh na Senórach,

https://celt.ucc.ie/published/G303000/index.html

(14) Murray, The Early Finn Cycle, pg.

For the overlap of traits that characterize Oisín and Caílte, see Murphy, pg. lix n. (1)(2)

https://archive.org/details/duanairefinnbook03murpuoft/page/n63/mode/2up?q=Sen-garman

(15) Bondarenko,

https://www.academia.edu/5295503/FINTAN_MAC_B%C3%93CHRA_IRISH_SYNTHETIC_HISTORY_REVISITED

(16) ibid.

(17) Arsaidh sin a eoúin Accla, ln. 81, Eachtra Léithín,

http://www.shee-eire.com/Magic&Mythology/Myths/Gaeilge/Colloquy-of-Fintanetc/Page1.htm

http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/leithin.html

(18) Parker, Culhwch ac Olwen,

(19) Meyer, The Quarrel between Finn and Oisín, pg. 25

https://archive.org/details/fianaigechtbeing00meye/page/24/mode/2up

A fascinating read! Thanks for sharing this! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Bon Repos my friend! Thank you so much for reading, I’m glad you enjoyed it. How did the goose turn out?

LikeLiked by 2 people

I did!!! 🙂

Ha, it was good but far too much 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Tiege,

Happy National Fruitcake Day!

I only know “Rhiannon” from Fleetwood Mac. And then I looked it up and Stevie Nicks was into this Welsh witch/goddess. I’m shook! Apparently, I need to delve into mythology.

I’m intrigued and need more details on “the hero summons his illicit lover by casting wood chips down a stream.”

I wish I had further insight on all these stories. Thanks for introducing me to new worlds!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Sum! Thank you for reading and the great comment!

I didn’t know Stevie Nicks was into Rhiannon! … I actually don’t know much about Fleetwood Mac, lol. I’m actually working on a post about Rhiannon, but it hit a bit of a snag. Lol nothing’s easy!

Oh thanks for asking, I’d be happy elaborating regards Tristan: the romance of Tristan and Iseult was a popular story from the 12th/13th c. about the doomed love affair of the knight Tristan and princess Iseult, the fiancée of his uncle, King Mark, after they (usually accidentally) drink a love potion together. Two ‘strains’ of the story survive, the ‘common’ and ‘courtly’ versions. A motif found in one of the ‘courtly’ versions contains an episode where Tristan signals to Iseult to meet him by spreading wood chips on a stream, which is found earlier in Irish. It’s been noted that certain Finn tales resemble T&I, but I’d like to make a post myself, lol.

Thanks again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for liking my posts, which has led me to looking into and now following your blog!

The comparisons with other tales is right up my street and I look forward to reading more of your posts.

Here’s hoping you enjoyed your cake and blessings to you for the New Year!

Locksley. 🖖🏻😃

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, and thank you for reading! I’m looking forward to reading more of your stuff too! Feel free to comment with any criticism or suggestions! Happy new year!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome! 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this interesting survey, in particular the Irish links. . Gruffydd’s book ‘Rhiannon’ has for long been a seminal text for me. He argued for an equivalence between Mabon(<Maponos) and Pryderi in the First and Third Mabinogi branches and so between(Modron (<Matrona) and Rhiannon. I summarise his argument here:

https://rigantona.net/rhiannon/rigantona/

Interesting that you found that old post on the now legacy 'Gorsedd Arberth' blog. I should re-visit that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Greg, thank you for reading! It’s gratifying to hear that you enjoyed it. Gruffydd is very compelling, thank you for the link, and yes, I think you should revisit the Gorsedd Arberth site, especially if it means new insightful posts!

LikeLike